Wine in the Roman culture between the 1st century B.C. and the 1st century A.D.

Introduction

This article will briefly summarize the culture of wine in Rome, focusing between the 1st century B.C. and the 1st century A.D., the period that corresponding to the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire. I will quote literary and historical records by contemporary writers and compare them with archeological evidences of the same period.

These two centuries are considered the golden age of Roman civilization for that literature, art, economy and military power have reached their peak in history. It is also a period that role of wine changes dramatically in the Roman society. In the previous centuries, wine was considered an imported and exotic product, related to the Greek influence on Italy. Even though, wine was already produced in the Italian peninsula, particularly in the South where there were many important Greek colonies. It was still considered as something exotic to the Italian traditional culture. During the 2nd century B.C., mainland Greece was conquered by the Romans, so that Rome had more and more influenced by the Hellenic culture, until at the end of the 1st century B.C. Rome considered itself a Greek city; even more, Rome considered itself as the city that inherited the tradition and the heroism of Homeric Greece. In the minds of court poets, Rome is the new Troy and the Roman Empire is seen as the “rebirth” of Troy, whose fallen was celebrated by Greek poet Homer and recalled by the roman poet Vergil.[1] Furthermore, in the imperialistic ideology, Rome had the right to conquer Greece as a vindication of Troy, which was destroyed by Greeks in a disloyal way with the famous trick of the Troyan Horse. Following the example of Vergil, all the poets and historians, who want to celebrate Augustus the first Roman emperor, refer him as the descendant of the Troyan hero Aeneas and they refer Rome as the “daughter” of Troy.[2]Consequently, all the Roman aristocrats who followed the emperor's path openly and proudly followed the Greek fashion and lifestyle-- studied in Athens for at least one year of their lifetime and showed themselves as refined Hellenic cultured men. Athens, Alexandria and Pergamum were the most prestigious cultural “capital cities”even in the Roman Era. A famous Latin sentence mentions Graecia capta, victorem cepit: “Greece, which was conquered, conquered the winner” meaning that Greece conquered Rome with its culture, even though Rome had conquered Greece with its soldiers. Under this new cultural context, the production, consumption and the social appreciation of wine in Rome changes completely.

Romans and wine: from the initial concerns to the appreciation and appropriation

Romans received the techniques of cultivating grapes, shaping vineyards and producing wine from Middle East, particularly from Greece. In ancient time, Roman wine wasn't really considered a national product but was seen as something coming from the Greek cultural area. The Roman god of wine is Liber Pater, which then took a Greek name, Bacchus, a Roman deity which had a Greek origin and is identified with the Greek god Dionysius, whose worship was introduced to Rome at least since the 4th century B.C. Still in the 2ndcentury B.C. a law known as Senatus consultus de bachanalibus[3] “A decision of the Senate about the ceremonies of Bacchus” shows the concerns of the Senate about this religion coming from Greece. Thierney points out that this law doesn't really forbid the worship of Dionysius in Rome but wants it to be under the control of Senate and political authority.[4] This text also forbid Roman citizens, Latins and socii, citizens of cities officially allied with Rome, to become priests of Dionysius. Thierney concludes that “there is no difficulties in establishing the existence of a strong party in the Senate at this period which was very hostile to the introduction at Rome of foreign and un-Roman religions.”[5]

Many conservative aristocrats and politicians warned the Romans that more and more influential Greek culture and Greek rites, including the worship of Dionysius related to wine could destroy the identity and morality of ancient Rome. Also wine could be an enemy of mos maiorum.[6] The historian Livy confirms the use of wine during the rites of bacchanalia (pictures 1 and 2).

Wine was also considered dangerous for the morality of women: the historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus believes that the first mythical king of Rome, Romulus, promulgated a law preventing women from drinking wine because “drunkenness causes adultery, and adultery causes madness”. Punishment could be very severe and the historian says that many women were sentenced to death.[7] Valerio Massimo thinks that the reason of the prohibition of drinking wine for women is due to the worrying about women's honour: wine was always linked to the illicit sex. A very ancient law, called IUS OSCULI (the law of the kiss) records that women had to give a kiss on the husband's mouth every day: this law doesn't have any romantic meaning. The reason is that Roman men had the right to check if their wives had any alcohol smell everyday, as this could be considered a real crime. The laws ruling the institution of family were always worrying about wine, since this was linked to the Dionysiac orgy and promiscuous sexual relationship: in a house where wine was common and easy to reach, descendants and family genealogy was in danger.[8]

At the end of the 1st century B.C. the attitude of drinking wine changed completely. Wine is considered a traditional product of Rome and it is strictly connected with the Roman identity and culture. The court poet Horace celebrates the victory of the first Roman Emperor Augustus on his enemies which were the rival Antonius and the queen of Egypt Cleopatra with the ode Nunc est bibendum (Now we have to drink). In this poem wine doesn't only refers to the “cheers” for the Emperor's victory: wine becomes a symbol representing Rome (Greece was already part of Roman empire) in contrast with the Egyptian wine, considered not good and dangerous for the human brain. The poet mentions one of the most famous wine produced in Italy, the Caecubum, saying that “it is now the moment to take the Caecubum from our fathers' cellars to celebrate and praise the gods” for the victory of the Emperor who brought peace and let the Good win against “the pride and madness of the foreigner queen (Cleopatra) whose mind was blinded by the Mareoticum (the Egyptian wine).”[9]

Horace also mentions wine in many poems: wine is no longer related to something sinful or orgiastic; in his poems wine is related to the warmth of the house and particularly to the friendship and the pleasure of sharing time with friends, chatting while drinking wine.

A whole poem composed by Horace is dedicated to the wine: the poet explains the right attitude of a noble man towards the wine. [10] The poet talking to Varo, another poet of the Augustus' court, mentions the most beautiful town in the countryside surrounding Rome, Tibur, where aristocrats used to have their villas and country palaces.[11] The poet describes the peaceful and warm atmosphere welcoming Varo, when he goes back to his countryside house, among olive trees and vineyards. In this relaxed evening, a particular joy is given by wine, which allows to forget the sorrows and the difficulties caused by war and politics. In this moment, the aristocrat can worship Bacchus, the god of Wine, and Venus, the goddess of Love. However, an aristocrat must always control himself. In fact, the poet says that the most important virtue of a noble man is moderation and self control. So, a Roman should know how to enjoy the “gift of Bacchus”without exaggeration. The pleasure of wine is before getting drunk and it is possible if you don't become drunk. The poet says that it is very dangerous for a politician being drunk since he may take dangerous and irrational decisions, as well as revealing important secrets. The poet gives all these suggestions indirectly, mentioning Greek mythological episodes about Lycurgo, kings of Tracia, and the war between Centauruses and Lapiti.

Even the most important poet of Augustan age, Vergil in his poem Georgics, talking about Italy's countryside and traditional roman farms, considers the olive trees and the vineyards the most representative cultivations of Italy. These cultivations should be the most important parts of every aristocrat’s family, as well as grain and the farming of sheep, cows and bees.[12]

In many writers wine was also seen as the typical drink of Romans, differently from the barbarians of the North, the Celts and Germans, who were connected with the beer (in latin cervisia).

The most ancient Roman books teaching how to cultivate vines and produce wine

The cultivation of grapevines was very ancient in Italy, but Romans started to produce a larger quantity of wine and develop more advanced techniques of vineyards through the influence of Etruscans and Greek colonies. In archaic Rome, the best wines were considered to be Phoenician and Greek.

An important document regarding vineyards in Rome belong the writer Marcus Porcius Cato who wrote an instruction book on agriculture, De agri cultura in Latin.[13] A whole section is dedicated to the cultivation of grapes: Cato thinks that if Romans want to create vineyards in their farms, they should follow the example of Greek farmers, particularly those of the Aegean islands. This writer also recommends to produce wine following the example of Cos, a Greek island whose wine was considered the best in all the Mediterranean.

In the previous paragraph, we saw that Cato the Elder was unfavorable to the Greek influence. So, why does he recommends to follow the Greek example, producing vineyards and wine copying the Greek techniques? The point is that Cato, as many Romans were very pragmatic and practical: he knew that at his time, wine and olive oil were the most important part of Roman economy, because these products were very much in required. This writer recommends other aristocrats to plants olive trees and vineyards in their lands because these are the most productive and profitable plantations. He thought that Roman landlords could become richer producing and selling wine instead of importing it.

According to the writer Pliny the Elder, Italian wines had started to be appreciated as the wines from Aegean islands since the first half of 1st century B.C.[14] However, Roman aristocratics thought Italian wine couldn't compete with Greek wine for what regard the quality: Roman farmers started to win this “economic war” producing more and cheaper quantity of wine. This wider production made the wine more popular and affordable to the common people, even to the slaves. Italian wine started to be cheaper but more popular and sold in a huge quantity.[15]

Romans imported different vine varieties from the Middle East and Greece. They planted their cultivations not only in Italy but also in the Western Roman Provinces, particularly Southern Gaul (Provence), its climate was very similar to central Italy. At a later time, they selected vine varieties which were more resistant to cooler climate and they spread the vineyards to central Gaul (France) and even to Britannia (England). After this huge implementation of wine productions and differentiation of vine varieties, in the different lands and climates of the Roman Empire from Britannia to North Africa, from Spain and France to Syria. Pliny listed 195 types of wines produced in the Empire. 50 of them were defined “generous”, 38 “foreigners”, 18 “sweet”, 64 “aromatized” and 12 “prodigious”. This richness in wine production had a first stop with the emperor Domiziano who, in 95 A.D. forbidded the creation of new wine yards in Italy in order to expand the cultivation of corns and cereals.

In the 1st century B.C. the Campania, the region of Napoli, is the land which produces the best wines in Italy. The poet Horace, mentioned above, writing to a very important politician, Maecenas, who was the most important secretary of the emperor Augustus, mentions the four best wines, which are all from Campania: Caecuban wine, Calenun wine, Formianun e Falernian wine.[16] The Falernian wine (falernum) was the most popular wine at that time. Pliny the Elder considers it the best wine at this time and he mentions there were three varieties of this type of wine: austerum (dry), dulce (sweet), tenue (mild).

Another writer, Atheneus of Naucratis, suggests that the Falernian wine should be tasted after an ageing of at least ten up to twenty years; the poet Martial refers that “this is an immortal black wine, it becomes older but never dies”.[17]

How Romans used to drink wine: different ways of drinking wine in the different social classes

The cheapest roman wines had a lower alcoholic gradation, so they could easily become acid, like vinegar. The most luxury wines, on the contrary, were first boiled, then they could age for many years, even decades and decades. At the end they became very dense and strong and Romans used to drink them mixing those aged wines with 50 % of water, at least.

Romans were very proud about the fact that they could produce wines which could survive for many years, without any change in taste and smell.[18] The famous writer and politician Cicero, wrote that he found in his storage a wine a hundred years old, which was still fine. He said that this wine stayed in a barrel in the fumarium, an area under the roof and over the oven, used to absorb the smokes from the kitchen. The constantly higher temperature coming from the kitchen and the wooden smoke around the barrels gave the wine a very strong aroma, coming naturally from the grapes fermentation and the wood of the barrels.[19]

So, beginning from the end of the 1st century B.C., wine is very popular even among poor people: wine starts to be produced in an “industrial” way, a way which brought to very big quantities but very poor quality. It was sold commonly in tabernae, local shops or simple restaurants in all the Roman cities.[20] The customers, sitting or standing in front of the desk could choose among different varieties of cheap wine, ready to be served and drank.

The way of consuming wine in the domus, the rich houses of wealthy people and aristocrats, was very different. Before serving wine in the banquets, slaves used to filter wine in linen bags or filters made of reed. These filters were impregnated with aromatic oils. In this way servants could separate pure wine from sediment, grape skin or seeds fragments, dust or terracotta vases fragments. The filtered wine was then mixed with water in a particular vase called krater, a large terracotta vase specific for this use. Even the best wines were mixed with water because roman wine was very dense and had a very high alcoholic concentration.

So, servants had to pour wine from amphorae, the very long shaped terracotta recipients where wine was stored, transported and traded, into the kraters, large painted and refined vases. Since kraters were very refined vases made of good quality clay and painted with many decorations and Greek mythology scenes, they could be brought into the banquet hall. Well dressed and polite servants of the banquet, who were often young and good looking, had to serve wine from the kraters to the guests' cups, using different utensils: the sympulum, a long spoon, a ladle, for taking wine from the krater and filling up smoller jars, called olpe or oinochoe; using these jars, servants could pour the wine into guests' cups, the kantharos or kylix.

All these different types of terracotta vases and cups have a greek name because they followed the Greek fashion of symposium, the banquet for heroes and gods. These vases were also very refined and all of them were painted with Greek mythological scenes in Greek painting style.

The amhporae didn't have any decoration because they were used for the transportation, trade and storage of wine. However, each amhpora had a pyttachum, a label carved into the clay, reporting the name of the producer, the provenance and the year of the contained wine. The amphorae were then closed using corkwood and pitch, so that the air and oxygen couldn't get into the container and ruin the wine. In every rich house, a special servant called the arbiter, (litterally the “judge”) an ancient sommelier, had to know the content of each amhpora and know exactly the different types of wine stored into the house, so that he could serve the right wine, following the whishes of the guests.[21]

There were different types of amhporae. The ones used for the transportation could contain 20 litres of wine; other bigger anhporae, or a larger version called dolia, could contain 200 up to 300 litres of wine and they were used for the wine fermentation. All these bigger recipients had an internal covering made by waterproof plaster. They were often put into the cold water to keep a lower temperature and consequently a slower fermentation. In the Alps regions, according to the writer Strabo, Romans preferred to use wooden barrels instead of terracotta dolia. Cicero showed us another way of storing wine in the barrels put on the roof, into the fumarium, in order to reach a quicker fermentation. The cheaper wines were kept in the same doliumfor the whole process of fermentation, whereas the more expensive and better quality wines were poured time to time in different dolia, so that they could become purer and loose the sediments.

In the 1st century A.D. the wine trade was very active in the whole Roman Empire. Reading the pyttachum, the label carved on the amphorae, archeologists could see that wine produced in South Italy was sold in South England, North Africa, France and Germany, whereas Italy imported wine from all the regions of the Empire, such as Spain and Brittany in the West or Greece and Syria in the East.

Conclusion

This article shows how much the wine production and consumption changed in the last period of the Roman Republic. It also shows different aspects of this change: the social consideration of wine, its representation in art and literature, its transformation into a status symbol for aristocrats and then a popular product for a “globalized” market.

Furthermore, the article explains the various functions of utensils and the procedures used in the production and consumption of wine. In the two centuries in my study, it appears that the Roman market of wine was fully developed and it showed many modern aspects: first of all, it was a global market. There were different methods of producing wine in order to target different levels of customers. Moreover, wine import is integrated with wine export in order to enlarge the selling market (picture 5). Finally, the aristocratic lifestyle inspires a popular market of common people who want to imitate the upper society.

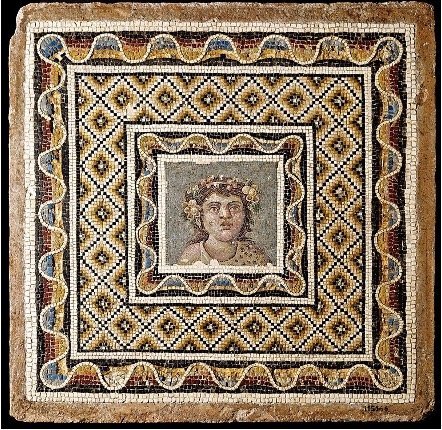

Pic. 1

Roman mosaic representing Dyonisus with grapes and vines in his hair.

Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome

Pic. 2

Roman scultpure representing Dyonisus with a cup and an amphora, a recipient for wine.

Museo Borghese, Rome

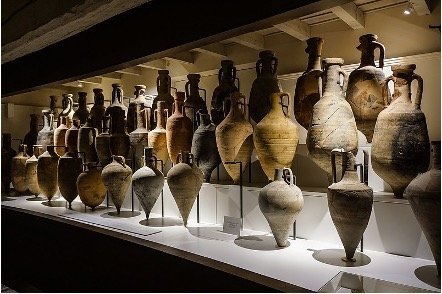

Pic. 3

Amphorae found in a Roman ship

Collection of the “Museo del Delta Antico”

Pic. 4

The taberna discovered in Pompeii on 28 December 2020

Picture from the press website www.arstechnica.com

Pic. 5

A fresco from the taberna in Pompei shows wine amphorae stored in the shop, in front of pots of food.

Picture from the press website www.arstechnica.com

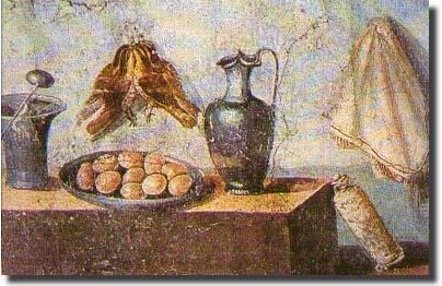

Pic. 6

Fresco in Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, a kitchen with tools and vases.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

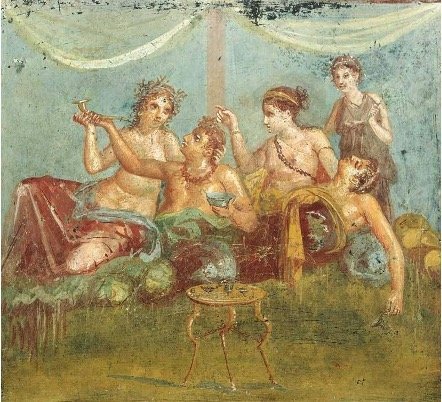

Pic. 7

Fresco in Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, a banquet scene with wine cups.

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli

Picture 8

Roman trade routes and principal products in each reagion, from the website:

www.vividmaps.com

[1] These ideas are expressed by the Roman national poem “Aeneis”, by the latin poet Vergil. The poet tells the story of Aeneas, who, escaping from Troy destroyed by Myceneans and other Greeks, arrives in Italy. The son of Aeneas, Iulus, is considered the ancestor Iulius Caesar, Augustus and the whole Iulia family, the first family ruling the Roman Empire.

[2] See Ovid and Horatius, historician Livius.

[3] This law, of the year 186 B.C. was mentioned by the Roman historician Livy (Livy 39,16-18), is also directly known by ancient epigraphs. See Annarosa Gallo, Senatus consulta ed Edicta de Bacchanalibus: documentazione epigrafica e tradizione liviana, in Bollettino di studi latini, fascicolo II, luglio-dicembre 2017; CIL I 581 = ILS 18.

[4] J. J. Thiernay, The senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus, in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature Vol. 51 (1945 - 1948), pp. 89-117

[5] J.J. Thiernay, ibid., page 94

[6] Mos maiorum means “the behaviour of our ancestors”; it is an expression which indicates the complex of values and social rules of the most ancient aristochratic Roman society. The most important author expressing thiese ideas is Marcus Porcius Cato or Cato the Elder(234 B.C. - 149 B.C.), particularly in his book Origines.

[7] E. Cantarella, I supplizi capitali in Grecia e a Roma, BUR, Roma, 2000; Eva Cantarella, Passato prossimo: donne romane da Tacita a Sulpicia, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1996.

[8] E. Cantarella, Ibidem.

[9] Horace or Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65 B. C. - 8 B.C); Nunc est bibendum, Odes, I, 37, 1

[10] Horatius, Carmina, I, 18.

[11] Tibur, the modern town of Tivoli, famous for the Imperial summer palace of the emperor Hadrian, built in the II century A.D.

[12] Honey was very important for the roman alimentation used instead of sugar and also used as a preservative. Honey was also used to produce sweet wine. Bees were very important for the fruit trees pollination and, in Vergil's poem, they became a religious symbol of purity, rebirth and immortality. See Vergilius, Georgics, book IV.

[13] This work of Cato the Elder dates back to 160 B.C. according to Alexander Hugh McDonald in his article for the Oxford Classical Dictionary.

[14] Gaius Plinius Secondus or Pliny the Elder (23 A.D. – 79 A.D.), Naturalis Historia.

[15] Alessio Garofalo “De rerum vinorum historia”, Alma Mater Studiorum, Università di Bologna, 2019.

[16] Quintus Horatius Flaccus, Carmen Saeculare, 17 B.C., liber X.

[17] Alessio Garofalo, Ibidem.

[18] Columella, De re rustica.

[19] Alfredo Antonaros, La grande storia del vino, Pendragon, 2000.

[20] The last discovery in Pompeii, happened on 28th December 2020, is a very interesting and well preserved example of a Romantaberna, see picture 4)

[21] Many Romans banquests were described by Emperial era writers such as Seneca the Younger, Petronius and Tacitus. Many mentioned objects were found in particulary in Pompeii and Ercolano.